Health & Education

Listening session explains immense task of unearthing boarding school records

By Nicole Montesano

Smoke Signals staff writer

The work is mundane and grueling; hours of combing through an endless succession of boxes of old records and digitally scanning each one, handling the fragile, aging paper with care to keep it from disintegrating.

But those documents, buried for decades in government archives, are vital. They contain the disturbing records of thousands of Indigenous children, torn from their families and enrolled in boarding schools to be stripped of their language and culture. Abuse was rampant and the survivors emerged traumatized. A legacy of broken families, health problems, alcohol and drug addiction and suicide followed.

On Thursday, Oct. 17, members of the National Boarding School Digital Archives, which is run by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, visited the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde to talk about their work in bringing school records to light. The group’s purpose is to create a national collection of boarding school records for survivors and their descendants to use.

Tribal Librarian Kathy Cole said the group reached out to her last January about coming to Grand Ronde, after an author she knew gave her name to the group. Cole scheduled the listening session as part of the library’s schedule of events. It took place the week after a screening at Spirit Mountain Casino of the documentary film “Sugarcane,” which reveals the abuses at a Catholic-run residential school in Canada.

The Grand Ronde Canoe Family drummed and sang before the presentation, and Tribal member Bobby Mercier gave the invocation in Chinuk Wawa.

Archive staff Fallon Carey (Cherokee Nation), River Freemont (Umonhon/Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa descendent), Tsinni Russell (Dine) and Ekoo Beck (Blackfeet, Red River Metis, Little Shell Chippewa) said they are all the descendants of boarding school survivors, a legacy that drove their decision to work with the archive.

The abuses are more recent than some realize. The boarding school era, when genocidal assimilation policies were in effect, is defined as 1801 through the 1970s — less than 50 years ago, Carey told the audience.

But news accounts about abuses at Chemawa Indian School were appearing in newspapers as recently as the 1990s, and troubling allegations have been raised in recent years. Although most boarding schools closed, a few, like Chemawa, remain open, under different policies that at least ostensibly respect students’ cultural backgrounds.

So far, Carey told the audience, the coalition knows of 521 boarding schools that were operated in the United States. The archive’s work is grant-funded and Carey said it is always seeking more grants.

It is primarily government records the archive is focusing on, because of lack of cooperation from churches, Carey said, although there has been some recent assistance from Quaker organizations.

“We have kind of exhausted the options we have,” she said.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition is seeking to get two bills passed by Congress, which would establish a Truth and Healing Commission and enable the group to subpoena the records of churches who ran at least 102 of the boarding schools known to have existed in the United States.

“It will open the floodgates of what we know the churches did,” she said.

On Friday, Oct. 25, the U.S. government took a step forward after President Joe Biden issued a formal apology for the country’s longstanding policy of formed assimilation of Indigenous children. It was the first time a U.S. president has ever publicly apologized for the devasting boarding school policies.

Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley sent out a press release to Smoke Signals and other media outlets following the apology.

“The government’s actions tore children from their families and communities and removed them from their culture,” he said. “We need to learn from the mistakes of the past and continually consult Tribal communities to fully repair this lasting, generational damage. As chair of the Senate Interior Appropriations Subcommittee, I have secured $21 million to date for Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s Indian Boarding School Initiative to examine and help repair these devastating, historic wrongs. I’ll keep fighting to secure funding for this important initiative and to uphold our commitment to honoring the solemn promise that the United States has made to Tribal communities to fulfill our trust and treaty obligations.”

Approximately 408 boarding schools were financed and run by the American government. Government records can be obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

Among the many disturbing discoveries researchers have found are letters sent from parents that apparently were never given to the children, and letters from the children to their parents.

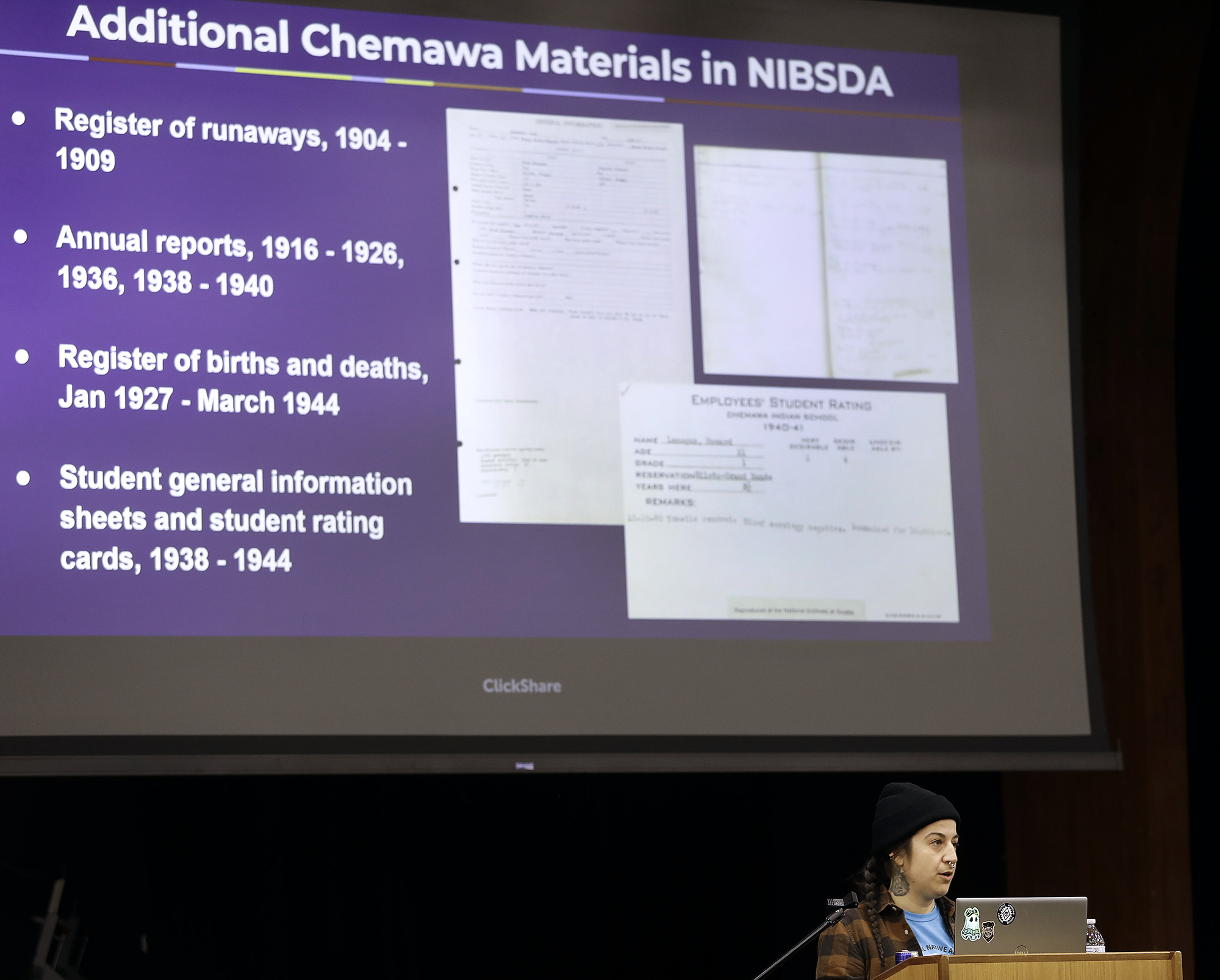

The records of the National Indian Boarding School Digital Archive are open for public searching, at nibsda.elevator.umn.edu, for survivors and their descendants.

Under the “what’s new” tab, it includes a Finding Aid section for people seeking information about relatives who attended Chemawa Indian Training School in Salem. Carey noted that all of the records are prior to 1949, because the archive does not collect material about people who are still living.

According to an archive maintained by Chemawa historian SuAnn Reddick and archivist Eva Guggemos at Pacific University of Oregon, at least 270 students died in the custody of Chemawa or its predecessor in Forest Grove.

No one actually knows how many records of the schools exist, although it is known that some are lost to age and poor conditions. Records have been destroyed by floods, abandoned in buildings that were later destroyed and otherwise lost to history, Beck said.

“Quakers were the only ones willing to work with us,” among religious organizations in the United States, Beck said.

“Quakers were the main pushers of the boarding schools, because they believed it was the best way to help Indians,” Carey said.

The federal government, however, saw a different opportunity in the idea, she said, including a chance to seize land belonging to students’ families.

The archive’s work is “going to paint a really large picture of the boarding school system and how the policy was applied,” Carey said.

One of its goals is to show which administrators were most involved, many of them at multiple schools across the country.

One aspect of the story was the practice of sending students out to work on farms and as maids in the community.

“They were training these students to be a subclass of laborers so middle-class white people could profit from their labors,” Carey said. “It was another form of resource extraction.”

She said she traveled to one location where a woman said a local church had been bulldozed with the records of the associated boarding school still inside.

“She and other Tribal members grabbed what they could,” Carey said. “I think a lot of records are going to be very incriminatory.”

Some records have been lost to negligence, Russell noted, such as being left in basements that flooded.

Beck said that some of the people who worked in the boarding schools are still alive and that increases the urgency of compiling records about their involvement and their roles.

“People ask us, ‘What’s the plan there?’” she said. “Our (Congressional) bill is step one.”