Culture

THE SALMON SITUATION: part one

Editor’s note: Salmon, rain and conifer forests are symbols of the Pacific Northwest. In a three-part series, “The salmon situation,” Smoke Signals examines how the region’s signature fish is heading for extinction, with little time left to reverse course and save these ancient species, which are crucial to both the ecosystem and Tribal culture. In the end, the Tribe’s best hope to prevail may lie in winning an epic battle with bureaucracy.

Parts two and three will run in the editions of Jan. 15 and Feb. 1, respectively.

By Nicole Montesano

Smoke Signals staff writer

For more than 5 million years, salmon have played a key role in the ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest, providing food for wolves, bears, eagles, sea birds, gulls, orcas, seals, sea lions and sharks, as well as people. Salmon carcasses littering streambanks after spawning provide fertilizer for riparian forests and aquatic plants, and food for insects.

According to the Canadian wildlife conservation group Pacific Wild, juvenile salmon are the primary insect predator in aquatic environments but after they die, their carcasses feed more than 60 species of insects.

“Salmon — that’s a keystone species,” Tribal Aquatic Biologist Brandon Weems said. “A lot of things depend on salmon, not just people.”

For at least 14,000 years, Pacific Northwest Tribal people have been part of that cycle, relying on the annual salmon spawning runs for high-quality protein and essential fat, to supplement the deer, elk, lamprey, tarweed seeds, camas, wapato and other first foods the region so bountifully offered.

Salmon, smoked to preserve during the winter, provided important nutrients and was a high-value item for trade.

Before the arrival of Europeans, or pre-contact, the landscape was well-suited for salmon production. Braided river channels across the broad Willamette Valley and surrounding mountain ranges provided numerous streams where salmon fry lived until they were large enough to make the journey to the sea. They could hide there in quieter water when storms churned the river, find plenty of insects to devour and less competition from the millions of their brethren. Gravel beds provided ideal spawning grounds.

European settlers radically altered that landscape, confining rivers to single channels, installing numerous dams to produce hydropower and control flooding, logging the trees that filtered, shaded and cooled the water, and draining wetlands for agricultural crops. The result has been catastrophic for Oregon’s iconic fish.

Without those calmer back channels, Tribal Hydrosystem Compliance Specialist Lawrence Schwabe said, the young fish get pushed out to the ocean when they’re much smaller and are subject to higher death rates.

The dams prevent young salmon from getting to the ocean and adult fish from returning to spawn. Few wild runs remain and those are down to a fraction of their historic numbers.

“Historically, Chinook runs were at 300,000 fish, now the 10-year average is 30,000,” Grand Ronde Fish & Wildlife Program Manager Kelly Dirksen said in the fall of 2024. “Last year (2023), the chinook rallied and they got to 23,422.”

Dirksen said the 2024 run was 21,989l.

Winter steelhead are in even worse shape: The 2024 run was 8,908, up from 2,039 in 2023.

“In a reasonable year, we see 5,000 fish return,” Dirksen said. “But in the winter of 2017, there were 780…It’s no longer sometime in the future that we could lose salmon. It’s in my generation, potentially under my watch and while we’re all still working.”

Both spring Chinook and winter steelhead are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Tribal Council member Kathleen George, a member of the Tribe’s Salmon Strength team, said experts believe these fish could be extinct within the next 30 years.

The assessments echo a report by the National Marine Fisheries Service published in July 2024, after it finished a 5-year review of the species’ status.

In a press release, NMFS quoted lead reviewer Annie Birnie saying, “The real issue is that they need safe connections to and from the high-quality habitat we know is above the dams. As long as they remain cut off, we’re unlikely to see signs of recovery.”

The agency estimates that the two species are at risk of extinction by 2040.

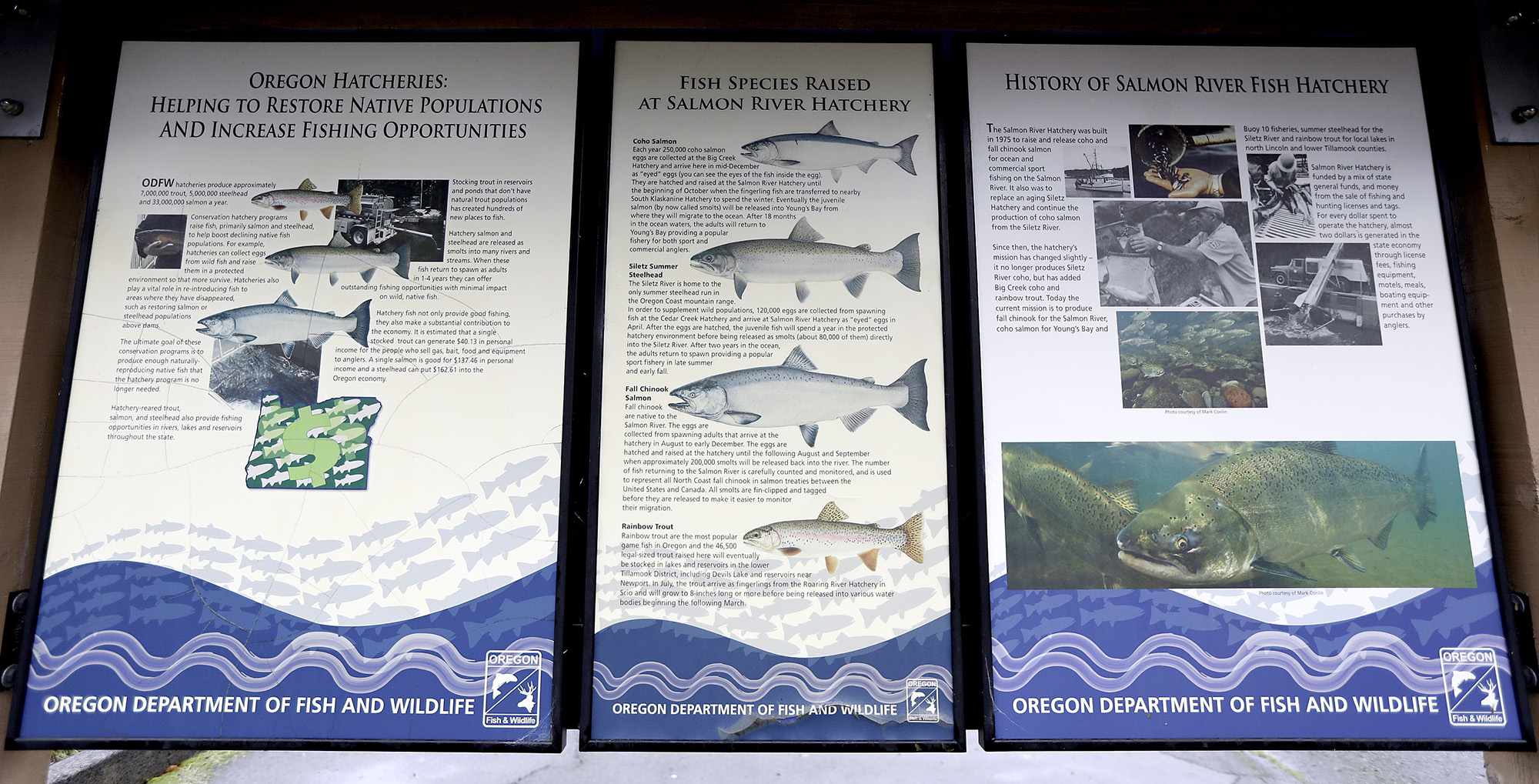

Raceways, such as this one that’s holding steelhead at the Salmon River Fish Hatchery in Otis, are used to raise hatchery fish. In 2023 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife hatcheries released more than 44,000,000 fish. (Photo by Michelle Alaimo)

Agreement on action, not on the details

Although there’s broad agreement that action is needed, the devil lurks where it always does, in the details hidden in the murky backwaters of politics, money and conflicting interests.

Finding a way to increase salmon survival is an issue that often divides Oregonians more than it brings them together.

Hatchery fish have been the state’s answer thus far but are a controversial subject. They provide almost all the salmon available for harvest, but are subject to genetic changes caused by the conditions they are reared in. They are also subject to catastrophic losses caused by human error or budget failures, and to the same environmental conditions that threaten wild populations.

According to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, 70% of salmon and steelhead harvested in the state come from a hatchery.

That’s important not only for the genetics of different fish populations, but also for the allies and enemies the issue can attract among various political factions, Dirksen noted.

In some cases, he said, hatchery runs can muddy the situation to casual observers.

“We’ve had a near-record run of summer steelhead in the Willamette, and sockeye in the Columbia this year,” Dirksen said in 2024. “But summer steelhead are not a native run in the Willamette. That’s purely a hatchery run. Winter steelhead, which are native to the Willamette, are not in any better shape.”

Salmon return to the streams where they are spawned, which leads to selective breeding.

“They’re adapted to the pathogens there, the temperatures, the flows,” Dirksen said. “Studies show that wild fish do have an edge.”

Hatchery fish sometimes dilute those genes.

“Still, it’s wrong to write (hatcheries) off altogether because they are what’s going to be needed to re-establish the populations,” he said.

ODFW Communications Coordinator Michelle Denahey said the state is facing some hard questions about its hatchery program.

“Our hatcheries have reached a tipping point,” she said. “Many were built in the 1950s and have a backlog of deferred maintenance.”

A nearby example is the Salmon River Hatchery in Otis, which needs a fish weir replaced for an estimated $12,000 to $15,000, but which is also increasingly vulnerable to flooding.

“We’re seeing increased water temperatures, which are a problem for rearing cold-water fish like steelhead, salmon and trout,” Denahey said. “We’re also facing, like everyone, inflationary pressures. For example, fish food costs are rising 5% each biennium and utility costs are also going up…Hatcheries are the single biggest expense of the fish division budget, about 40% of that budget.”

The agency plans to spend this winter compiling a report on hatcheries’ future viability for the state Legislature.