Culture

Book intended to help children face being different

By Nicole Montesano

Smoke Signals staff writer

Once upon a time, in a land that was not far away at all, but right here in the Pacific Northwest, there lived a people who were free to be entirely themselves – men, women, Two-Spirit, non-binary, whomever and however they might be.

But times changed and colonialism brought in another view – that gender is not a many-splendored thing, but inescapably binary. By the time Tribal Elder Qahir-beejee was growing up, to be identified by society as a girl was to be shut out of most things that interested them such as drumming, carving and participating in sports.

“I always thought there was something wrong with me,” Qahir-beejee said. “On another level, I was very happy not to be like everybody else. I didn’t like what ‘typical girls’ liked; to me, it was boring and dumb. ... but I was always getting the message that, ‘At best, you’re going to outgrow this. At worst, there’s something wrong with you.’”

Qahir-beejee, who identifies as gender-fluid and non-binary, has spent much of their life working to prevent other children from feeling the same way they did.

A few years ago, their longtime friend and colleague in early childhood education, Katie Kissinger, decided that their stories about the way binary gender roles have affected them should be more widely shared, for the sake of both children and the adults in their lives.

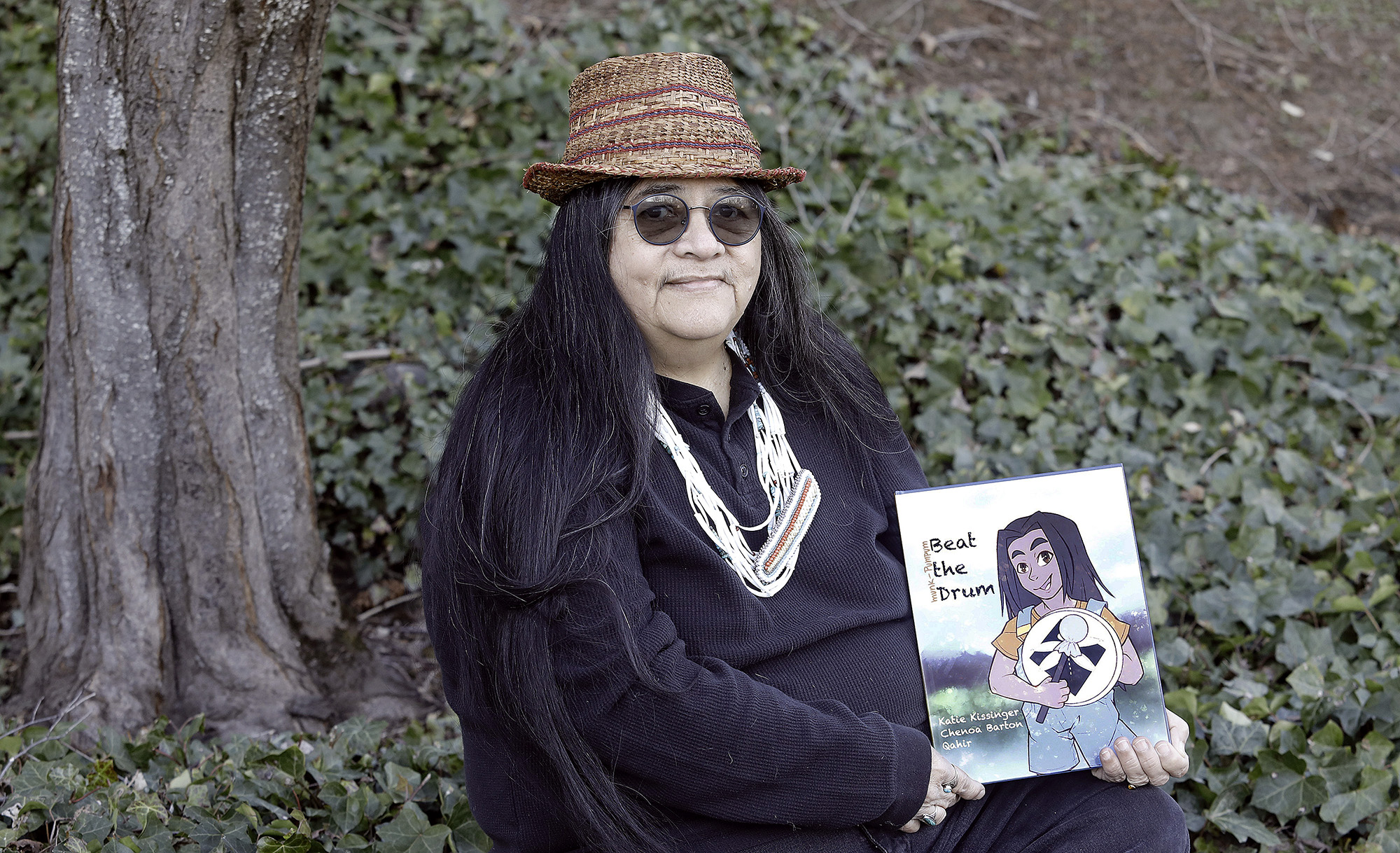

That was the beginning of a children’s book they wrote together; “Beat the Drum,” which tells the story of a girl who isn’t Qahir-beejee, exactly, but is perhaps who they could have been. Like Qahir-beejee, the girl in the book wants to pursue her own interests – things like drumming and carving – that are largely reserved for boys and men. And, like Qahir-beejee, she knows that while she is a girl, she is also more than that: She is Two-Spirited.

“The story is created based on the child she would have been, if she had had the support to be herself,” Kissinger said. “And I think it’s something as people who are working for justice and inclusion for all children, we want all children to be able to speak up for themselves, and feel the power, like the Overcomer does in the book.”

Both Qahir-beejee and Kissinger remain passionate about advocacy and early childhood education. Both serve on the board of the Threads of Justice Collective, which is dedicated to supporting young children in anti-bias education. The book continues that work.

“Oppression represents trauma in the lives of young children and it’s our job to teach children to resist the messages of society and to be allies to one another in that effort,” Kissinger said.

In addition, Qahir-beejee said, “We teach adults how to intervene on behalf of children,” so that they are not left feeling unsupported.

The book began with a poem, Kissinger said.

“I wrote a poem for an early childhood conference we were having. … It was a call to action for teachers and at the end I said, “If this child were in your classroom, how would you support them? How would you make sure they didn’t have to work this hard?”

Later, she decided to turn her poem into a children’s book.

Initially, she intended it to be a surprise and reached out to Qahir-beejee's granddaughter, Tribal descendent Chenoa Barton, to provide the illustrations.

“We got partway in and I remembered that my friend Qahir does not like surprises,” Kissinger said.

When Kissinger and Barton sought their approval, they said, “Once I got past the shock,” the idea was appealing.

“I like the message and I like the way it’s given, not in the dominant culture way but in a Native way,” they said.

They also found that they had something to add to the story. “Since it was a Native story and based on Native things that had happened, I wanted to add the chinuk piece, and I was in a chinuk class at the time,” Qahir-beejee said.

Friend and fellow artist, Tribal descendant Felix Furby, helped with the translations and often reads the chinuk wawa translations during story readings.

Both Qahir-beejee and Kissinger said they grew up hearing that they ought to be “ladylike,” something that didn’t interest Qahir-beejee in the least.

“I was really good at sports, which was supposedly atypical for a girl,” they said. “I was also really good in math, which was considered atypical for girls.”

Softball and tennis were among their favorite sports. Qahir-beejee lettered on the high school tennis team.

“Oftentimes I was the most valuable player in tournaments in softball,” they said. “I was fourth batter. So, it wasn’t just that I liked (sports); I was fairly good at them. But the message was always that it wasn’t ladylike, and oftentimes too, when I was going to school, you had to wear a dress or skirts. You weren’t supposed to wear pants. Often, I had shorts on underneath, so when I got home I would just pull my clothes off, and I had shorts underneath, and my dad was appalled because it wasn't ladylike.”

And yet, they believed the adults around them, who said they would grow out of their interests.

“So, I waited and it never happened,” Qahir-beejee said.

Instead, they went right on playing on sports teams, joining city leagues as an adult, teaching themself to drum and learning to carve.

The illustrations in the book reflect some of those realities, Kissinger noted, as these are informed by Qahir-beejee and Barton’s relationship.

“You can tell she knows and loves her grandma,” Kissinger said. “A lot are actual reflections of Qahir’s artwork – you see the actual drum (they) made, and the carving (they) did.”

But for all their determination to be wholly themself, there have been painful realities.

“I have drummed for the Tribe at other events but never at the plankhouse,” they said. “My grandson, when he was 5, I made him a drum and he could use that drum and drum in the plankhouse, and in fact, he drummed at his kindergarten graduation. But I would not be allowed to.”

Even today, they noted, ‘They teach the girls to dance and they teach the boys to drum; they teach the girls to rattle and they teach the boys to be drum singers.”

Qahir-beejee remembers when the Tribe temporarily stopped performing marriages in the early 2000s, in order, they said, to avoid making a decision on whether to perform same-sex marriages.

Watching the country increase in tolerance over several decades only to see today’s harsh backlash with the election of the new president has been painful, they said.

“Now it’s sanctioned, so anybody can feel encouraged and righteous about discriminating against people – it can lead from name calling and humiliation all the way up to physical violence,” they said. “It’s more painful and it’s more scary.’

But neither Qahir-beejee nor Kissinger have given up.

“I never would have guessed that we would be regressing in this way,” Kissinger said. “The book is way more controversial than it was when it was published, and so we're talking about trying to get the book into more places where there are kids who might be being targeted.”

Lessons like those in the book, Qahir-beejee said, provide “a way to build resiliency for people who are going to be targets when you are affirming that what they are doing is right, but that some people might not like it.”

Tribal Librarian Kathy Cole said she has ordered a copy of the book for the library. It is also available for purchase online at Lulu.com.